Between 2003 and 2017, Open Futures was conceived, developed with schools across England and became a powerful pedagogical framework for learning and teaching in Primary Schools. This timeline documents the development of the programme from a small pilot project working in a few schools, through the development of the Open Futures pedagogy and establishment of four related strands, and the ways these were then applied in different areas of the country.

Helen Hamlyn and the Helen Hamlyn Trust developed the Open Futures programme in line with its ethos for nurturing innovation by creating long term partnerships with expert organisations and individuals to create change. The proposition, which became Open Futures, was a programme for young children and their teachers, which would sit at the heart of the school curriculum, the school development plan and the school community.

“Paul and I shared a very strong commitment to social justice and to creating opportunities for those at risk of social exclusion. Education is the thread that connects every area of my trust’s activities. In all our education work we aim to address challenges and lack of opportunities.”

Lady Hamlyn

At the time schools had been subject to frequent successions of short-term government initiatives. In 2008, Christine Blower, acting general secretary of the National Union of Teachers, reflected that:

Headteachers and their staff teams who collaborated with the Trust and its partners did so because they shared a deeply held commitment and responsibility:

- to provide children with experiences that they may not otherwise be able to access

- to ensure that children discover their capabilities

- to ensure that children leave their school with achievements which will give them the skills and confidence for their ongoing learning and agency in their lives ahead.

"The evidence from the Primary Review is that 'initiative-itis' in primary schools has got in the way of teaching and learning, not to mention improving standards.”

In total, Open Futures benefitted over 70,000 primary aged children in the UK nationally and continues to do so. Beyond primary, Central Bedfordshire College continues to pioneer the Open Futures approach to learning and teaching in Further Education, and beyond the UK, Filmit continues to work with schools right across India in partnership with INTACH.

The Open Futures enquiry and skills-based approach to learning and teaching continues to be not only relevant but a powerful curriculum tool for whole school development, teachers’ creativity, children’s learning and parental and community engagement. Why not give it a try…

2002

Intro

2003–04

With growing awareness of the evidence supporting early intervention to help improve outcomes for young people, Helen Hamlyn and the trustees turned their attention to reaching young children at the earliest stages of their education.

The Helen Hamlyn Trust, already working in the field of education and welfare, was engaged with the problems of growing numbers of school leavers not in employment, education or training (so-called ‘NEETs’), re-offending rates of young offenders being shamefully high and an emphasis on interventions targeting secondary school age children. ‘Too little, too late’ was the feeling amongst charitable trusts and foundations. With growing awareness of the evidence supporting early intervention to help improve outcomes for young people, Helen Hamlyn and the trustees turned their attention to reaching young children at the earliest stages of their education.

“Encouraging children’s individual abilities at a young age is essential.”

Lady Hamlyn

Childhood obesity and a lack of knowledge about food and nutrition was causing serious health and wellbeing problems. With the emergence of digital technology came rising concerns about the effects on young children’s emotional and physical health. Alongside these issues, the aftershock of 9/11 was still being felt in schools and communities nationally. The themes for the trust were defining themselves.

- Closing the attainment gap

- Improving enjoyment and motivation to learn

- Reducing obesity and improving health

- Improving emotional and social wellbeing and personal development skills

- Improving parental engagement

- Improving community cohesion and engagement

- Increasing environmental awareness

The aim was to initiate a programme that would reach children at the earliest stages of their education, bring learning to life and, importantly, enable young children to discover and develop practical skills, personal interests and values, which would contribute to their education and empower them as individuals.

Curriculum

In May 2003, the Department for Education and Skills launched ‘Excellence and Enjoyment - A Strategy for Primary schools’, which sought to drive up standards with a range of measures including giving greater scope for primary schools to develop their own curriculum. It sought to reposition education as a service that worked for the benefit of individuals rather than as a basic standard that individuals had to adapt to.

2003–04, Setting the scene

2004

In the UK, research identified excellent school-based programmes relating to food, gardening and horticulture, but nothing which brought them all together and placed them at the heart of the school, the curriculum and children’s learning.

Extensive desk research was carried out looking into cultural and community cohesion programmes, food programmes, educational theory and creative pedagogies. These included John Dewey’s theories that children learn best when they interact with their environments and are actively involved with the school curriculum, and the Reggio Emilia approach, a pedagogy described as student-centred with principles focussing on self-expression, communication, logical thinking, and problem-solving. The ‘Every Child matters’ initiative launched with policies aimed at providing a holistic approach to ensuring children could thrive. In particular, initial inspiration was taken from Alice Waters’ Edible Schoolyard, which had started as an idea in 1995. In partnership with the principal at a public middle school in Berkeley, California, Alice Waters brought to life an organic garden, which then went on to flourish as a rich learning and teaching environment. A kitchen classroom was built, which brought everyone to the table to share what they were learning.

In the UK, research identified excellent school-based programmes relating to food, gardening and culture, but nothing which brought them all together and placed them at the heart of the school, the curriculum and children’s learning. As for creative digital learning programmes in Primary schools, these were in their infancy and few and far between in 2003.

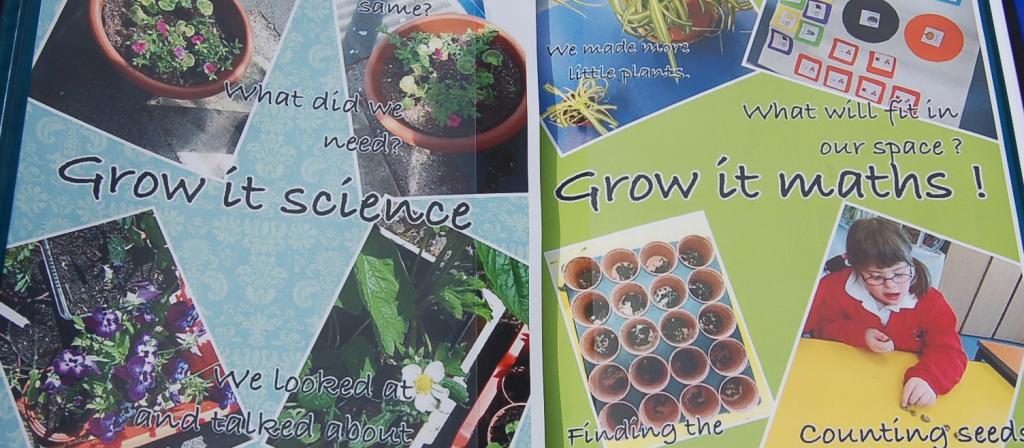

The Helen Hamlyn Trust wanted to develop an integrated cross curricular approach which would be central to how children learn. Food sits at the heart of every culture and brings people together. It had potential links right across the curriculum from maths to geography, art to literacy, science to PSHE and seemed like a good place to start.

2005: Concept and partners

2005

The Royal Horticultural Society and Focus on Food were invited to develop a teaching approach and supporting resources that linked growing food with preparing and cooking food.

Two leading organisations working with UK schools, identified during the research, were The Royal Horticultural Society and the Focus on Food Campaign. In 2004, The Royal Horticultural Society had only just begun, for the first time, to send horticulturists into a handful of schools in areas of urban regeneration and rural isolation. Focus on Food, meanwhile, had a national reputation for teaching cooking skills to more than 20,000 UK primary and secondary school pupils and their teachers. Both organisations were well established but at a pivotal point in their education strategies.

Lucy O’Rorke, Director of Projects for the Trust, met up with Anita Cormac, Executive Director of Focus on food, in a primary school car park in east London on board one of their specially-designed articulated lorries that transformed, Formula 1 style, into a fully equipped state of the art kitchen classroom. As two boys from Shipden said later, “The Cooking Bus was like Dr Who’s Tardis. When we went in it was a big modern kitchen inside – very posh! “

“A great strength of the HHT is in bringing together organisations and people in an innovative way. Had we been working alone as organisations, we would not have seen the remarkable benefits that Open Futures has on children’s confidence and love of learning.”

RHS and Focus on Food

Lady Hamlyn and Lucy O’Rorke approached the Royal Horticultural Society to ask if they would like to collaborate with the Trust and Focus on Food to develop a primary schools programme, which would connect the rewarding processes of growing, harvesting, preparing and cooking your own food. The Trust was clear that it wanted to integrate these activities into the school’s curriculum and children’s learning. This was not about after-school clubs or ‘school gardening’! This was about developing a programme and underpinning pedagogy with schools for schools.

Early Intervention

Although policies directed at very young children and their parents had been around in various forms since the nineteenth century, early intervention as a distinct Government policy approach only began to develop significantly from the 1990s onwards.

“Primary education is a critical stage in children’s development – it shapes them for life. As well as giving them the essential tools for learning, primary education is about children experiencing the joy of discovery, solving problems, being creative … developing their self-confidence as learners and maturing socially and emotionally.”

Excellence and Enjoyment: A Strategy for Primary Schools 2005

2004. R&D Phase – Who’s doing what?

2005–06

Following an open application process, ten schools in areas of deprivation on the South Coast were selected as the first Open Futures pilot schools. In September 2005 work got underway.

Ten Schools on the South coast were identified through an open application process to become the first pilot schools for the project. Schools signed up for a one-year pilot called growit cookit, which then became two years and continued on with new strands being introduced. Some of them are still running Open Futures today!

“It’s just what we do!” as one teacher said, “I can’t go back to the way I was because the way I teach has changed.”

The schools all had above average numbers of children receiving free school meals. The aim was to work with a variety of schools: some with outdoor areas, which could be developed into working kitchen gardens; but also schools with only window sills, tarmac and little outdoor space to ensure the programme could be accessible and responsive to needs.

“It makes us feel proud, like we’re actually good at something.”

Pupil, South Coast

In September 2005, RHS trainers worked with teachers, parents and children to design and build working growing spaces in all ten schools. The teachers, some of whom were understandably worried about the potential extra work this would require, worked with the RHS trainers. The biggest issues were how and where to establish and maintain the growing areas, how to manage a full class of 30 children and how to plan and manage what to grow when. Then there was weeding!

Focus on Food and the RHS looked at seasonal planning so that children could harvest, prepare and cook what they had grown.

Specialist trainers from Focus on Food began to work with the schools to identify appropriate spaces in which the children could learn how to cook. They looked at health and safety considerations with teachers and teaching assistants. For most of the teachers involved, the professional development provided was their first practical training in both horticulture and cookery teaching.

“We linked the Open Futures skills into the topic cycle, for example using different crops and recipes to teach about different religions and cultures.”

Teacher

Some initial cookit training took place on the Focus on Food Cooking Buses, beautifully designed fully equipped teacher training kitchens accommodating up to 16 teachers. Some sessions were also run for parents and children.

Listening to an early progress report on the cookit strand of the programme, Helen Hamlyn observed that schools would need their own cooking equipment to work with the children when the trainers were not in school. Her observation was the catalyst for the launch of the Focus on Food ‘Cookit’ - a set of high-quality cooking equipment designed to enable groups of up to 12 children to cook.

2005–06. First Pilot: growit cookit

2006–08

With new schools joining and the introduction of askit, the team of researchers and trainers at SAPERE used their experience in ‘Philosophy 4 Children’ (P4C) to shape askit and provide the underpinning pedagogy for the programme.

2006 to 2008 were incredibly active years of development for Open Futures. The growit, cookit programme was proving a great success. Children previously reluctant to go to school now attended regularly with enthusiasm to participate in all learning activities. The Trust decided to extend the programme to a further ten schools in Leeds and Wakefield from September 2006. Meanwhile two new strands were in developmeht to be ready for the new academic year: filmit and askit.

Askit

The Trust was seeking a way to help young children understand different cultural perspectives, given their very diverse multicultural environment. At some schools, over 40 different languages were spoken - creating spaces with a range of distinct values, beliefs and conventions.

.jpg)

Lucy O'Rorke, Director of Projects for the Trust, was interested in the potential for philosophy with young children, and discovered ‘Philosophy for Children’ (P4C), developed by Mathew Lipman. Philosophy for Children supported children’s communication skills, confidence to speak, listening skills, teamwork and self-esteem. Academic evaluations of the approach from the US, Australia, Canada and Northumberland had identified consistently impressive impact, with one case demonstrating sustained impact two years after children had stopped having discrete P4C sessions.

The Trust approached Roger Sutcliffe, founder of SAPERE, the UK charity for P4C, to discuss a possible place for P4C in the Open Futures approach. Askit would introduce enquiry-based learning and develop children’s skills to ask questions and think critically, creatively, collaboratively and caringly.

“The problem with the old slogan of learning through doing is that you can do and do and do and actually not succeed in learning because you’re either not asking the right questions or you’re not reflecting on what you’ve done and learning from your mistakes. Developing those basic skills, feeds not just into the strands of Open Futures but good learning across the curriculum.”

Roger Sutcliffe

Roger attended a training session on the cooking bus. The Open Futures team then hosted a meeting with the RHS and Focus on Food to introduce P4C and discuss the role it could play in Open Futures. The RHS raised the issue of low confidence levels among some teachers in the run up to a new school year. They were worried they wouldn’t remember everything they’d learnt.

Roger was interested by this challenge to increase teacher confidence through an enquiry-based approach. Enquiry-based learning makes the learning experience a shared enterprise, empowering children and teachers to become active participants in their learning.

The team of researchers and trainers at SAPERE would use their experience in P4C to shape askit to provide the underpinning pedagogy for the programme, connecting the practical manual skills of the other strands with creative, reflective thinking.

Filmit

Filmit was developed by interaction designers Andy Huntington and the late Andy Cameron to engage schoolchildren with technology in a positive and creative way. The idea of filmit was essentially to allow children to make video content and share it with one another online. (Another website with similar aspirations - YouTube - launched the same year!)

The filmit strand was developed to address a number of concerns: fear of the internet/privacy (the programme was based on a closed system with no public access); inconsistent levels of support and equipment (the Trust provided an iMac, custom software and a simple camera, and installed each machine); and teachers’ lack of time (the programme developed ways of working with groups and individuals on short films and longer projects).

Some schools made cookery and gardening films following on from growit, cookit. Others used filmmaking for art, English, drama and science. Teachers were given the freedom to work in ways that suited them. Filmit’s purpose was to support teachers and children in the creation and use of film as a medium for communication and learning across the curriculum. Filmit helped writing, communication, deepening understanding of science concepts and even extended as far as ‘Oscars Night’ to engage parents in their children’s learning.

Evaluation by Newcastle University

The Trust engaged an academic partner in 2007 to be sure that Open Futures was achieving its objectives effectively. David Leat, Professor of Curriculum Innovation and Executive Director of the Research Centre for Learning and Teaching at Newcastle University, joined the team. David was, at the time, the only Professor of Curriculum Innovation in the country and had a particular interest in enquiry-based approaches to learning. The Newcastle team carried out a formative evaluation to enable the Trust to progress the programme’s development effectively in real time.

Harnessing children’s natural curiosity

A review of studies by Professor James Dillon (1988, The Practice of Questioning, Routledge, p. 7) found that in an average school hour, at both primary and secondary level, the teacher asks over 80 questions, while the students, between them, ask just two. This review came shortly after a study (Tizard and Hughes, 1984, Young Children Learning, Harvard University Press) that indicated that 4-year-olds ask on average 20-30 questions an hour, but that this figure drops dramatically during the time they are in school.

2006-2008 An emerging whole school, whole curriculum approach

2008–10

A partnership with Wakefield MDC enabled Open Futures to work with a third of all primary schools in the district, who signed up for a two-year commitment to introduce the programme.

This was a chance to focus and consolidate what had been learnt during the previous three years. Hearing from staff at existing Open Futures schools was the most powerful means to communicate what the programme could offer schools and the impact it had.

A third of all primary schools in Wakefield signed up for a two-year commitment to introduce Open Futures across their schools. Hearing from staff at existing Open Futures schools was the most powerful means to communicate what the programme could offer schools and the impact it had.

“The quality of what they were coming out with, they’re posing questions and listening to each other. The impact on standards has been a really positive effect.”

Teacher

The Hub and Associate Schools model was developed to build capacity and get schools working together to share training, skills and build confidence.

Hub Schools hosted open days and invited colleagues from Associate schools to meet teachers and other staff, to spend a few hours seeing Open Futures in action. Teachers in the Hub schools contributed to the training in the Associate Schools and supported staff in the planning and implementation of the programme. The level of training provided by our specialist partners was reduced, becoming more collaborative and more targeted. A community of practice was evolving.

See the Wakefield Partnership briefing for more information about this stage of the programme.

2008–10 Working with Wakefield

2010–17

Open Futures expanded into urban areas of high deprivation, working with large primaries of up to 700 pupils.

The Open Futures Quality Mark was helping schools, to embed the programme sustainably as a key driver for the School Development Plan. The Open Futures flagship school award was introduced in recognition of schools tremendous achievements and creative practice. Flagship Schools demonstrated excellence and became the programme’s greatest ambassadors.

From 2010 to 2017 Open Futures expanded further by establishing new curriculum partnerships across four urban areas of high deprivation (Hull, Manchester, Birmingham, Newham). The majority of the schools were large primaries with up to 700 pupils. As with previous models, Open Futures extended out from Hub Schools, which introduced Open Futures to Associate Schools, and helped provide training.

Quality assurance

As more schools were taking part, and training decentralised, Open Futures introduced a Quality Mark to support schools to maintain standards in the teaching of the Open Futures strands and support schools to focus on their needs and the needs of their children. As well as contributing to sustainability in the long term, it helped the schools to feel ownership over the programme and how it worked in their context.

‘Pupils make rapid and sustained progress because of the highly personalised curriculum and practical nature of their learning.’

The assessment process for the Quality Mark was designed to facilitate professional development. Level 1 was self-assessed; Level 2 peer assessed and Level 3 independently assessed by an external party.

Level 3, Flagship School Status, required Open Futures to be firmly embedded as a key driver for the School Development Plan. It covered a range of requirements which were also designed to ensure the programme’s sustainability. Requirements included evidence demonstrating engagement of the management team and governors in supporting and reviewing development and teachers and TAs planning creatively to support pupils in understanding and applying a wide range of cross curricular skills to further their learning right across the curriculum and not just in discrete OF strand sessions.

Flagship Schools were introduced ion 2013 and by 2017, 36 schools had attained the Flagship status.

CPD offer

In 2016 and 2017, the programme also began to increase access to its training via a suite of CPD modules open to individual teachers, which also served as a vehicle to provide top up training for existing Open Futures schools and an introduction to the Open Futures approach for those new to it. CPD sessions were in the main hosted by Flagship Schools, which provided opportunities for learning walks and a chance to talk with staff.

Management structure

BY 2017, Open Futures was clearly articulated as an enquiry and skills-based learning strategy for schools to complement, extend and reinforce their existing educational curriculum backed up by evidence. With the help of the curriculum team, John Storey, Sue Macleod and Bob Pavard, the programme had developed organisational structures with key steps that proved successful for schools.

‘The careful planning of the curriculum tailors learning to match the pupils’ needs and match their curiosity.’

Headteachers and senior managers recognised the importance of a management structure for Open Futures, which embraced whole curriculum planning as well as the management of the individual strands.

The structure was made up of an in-school Open Futures Development Team of six to eight people who managed and supported an action plan to ensure that Open Futures was developed coherently and progressively throughout the school. They supported the development of the pedagogy, ensuring that the strands of Open Futures were not planned in isolation, either from each other or from other parts of the primary curriculum and ultimately informed the learning of all pupils within the school and across the whole curriculum.

As Ofsted inspection reports have said, ‘One of the key reasons for the improved standards since the last inspection is the school's imaginative and creative curriculum. This is exceptionally well planned to ensure that the curriculum is broad and links aspects of learning, for example, by providing real, relevant contexts for pupils to develop their writing skills. Teachers find practical ways to give pupils life skills which impact very well on their development, for example by growing fruit and vegetables and then cooking them in school. Pupils often work in pairs or small groups, and such approaches ensure that pupils develop personal skills alongside basic literacy, numeracy and information and communication technology skills which prepare them exceptionally well for their future education and working lives.’

See case study on Open Futures in Further Education

2010–17. Expansion and diversification

2017–18

The centre now provides a permanent physical and intellectual home for Primary and Early Years Education that brings together outstanding researchers, education professionals, parents and children to unite in the goal to improve outcomes for children aged 0–11 years, and provide access to learning experiences which are engaging, meaningful and effective.

In 2017 the trust took the difficult decision to cease delivery of the Open Futures programme to schools. Instead it sought to find a way to secure and extend Open Futures, to distil the essence of the programme, harness what had been learnt and ensure its ongoing development and impact. The Trust wished to establish a lasting legacy in the field of Primary and Early Years Education to create continual improvements in the quality of learning and life for young children at the earliest stages of their education, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The Institute of Education (now UCL Institute of Education) trains more teachers than any other provider in the UK and is respected globally for its long-standing expertise in early years and primary education, which has been shaping policy and practice for many decades. The Trust is thrilled that together we have established the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Pedagogy (0-11 years). The centre provides a permanent physical and intellectual home for Primary and Early Years Education that brings together outstanding researchers, education professionals, parents and children to unite in the goal to improve outcomes for children aged 0–11 years, and provide access to learning experiences which are engaging, meaningful and effective.

Research, and ensuring the translation of research into practice to improve quality of life, has been at the core of both the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design at the Royal College of Art and the Hamlyn Centre for Robotic Surgery at Imperial College. Both Centres take an approach that is inclusive, interdisciplinary and involves users. Likewise, the focus of the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Pedagogy is to improve educational practice through practical research using an inclusive approach and collaboration between education professionals, parents, carers and children. The centre at the IOE will facilitate this collaboration to innovate and create change on the ground.

Change is sustainable when it is a collaborative enterprise. In partnership with the IOE, HHT will be able to reach greater numbers of teachers to provide professional endorsement and practical support to access transformative teaching for children at the earliest stages.

"the focus of the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Pedagogy is to improve educational practice through practical research using an inclusive approach and collaboration between education professionals, parents, carers and children"

The Trust has achieved and learnt a lot through its close collaboration with its Open Futures' professional partners and schools nationally about what works, why and how. Importantly, it has also learned what the obstacles are to school development and impacts on children’s learning. The Helen Hamlyn Centre at the IOE will build on this learning by engaging world-leading research and international practice, enabling new approaches, relationships and change which extend the principles of Open Futures into something new with a much wider impact on learning and teaching. This is not something that the Trust could do by itself so the partnership offers a means to take forward the achievements of Open Futures through a different type of organisation with expertise to sustain it in the long term.

Becky Francis, Director, UCL IOE, writes: “It is now well-established that the quality of teaching has most impact on the learning outcomes and achievement of children, and that this is particularly the case for pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. As such, teaching excellence in the early and primary years is crucial for giving all children the chance for an equal start on their educational journey, and to address social inequalities in development and learning already evident by the early years. Yet, there remains very little direct focus on the quality of pedagogy and practice in the early and primary education years, and how this might be developed. Improving pedagogy through world-leading research and curriculum innovation would be a core focus for the envisaged Centre, making it globally distinctive. Given the resources and expertise of HHT through Open Futures, and of the IOE, we will be well-placed to deliver a Centre that is globally reputed for excellence as well.”

Get Involved

Join us on the next chapter and become an affiliate member of HHCP. We are building our network of practitioners. If you would like to become an affiliate member, keep up to date with latest news and events, or participate in future projects then e-mail: [email protected]